Identity Project by Vivian, Law Ho Man

I have long taken the idea of being a Hongkonger as natural and granted, but this has been shaken after a journey to the United States. I enjoy the days in foreign countries and am open to be acculturated and enculturated by a diversity of cultures. One unexpected side-effect brought by those encounters would be the estrangement of the idea of ‘self’, ‘ego’ or ‘self-identity’. With the facilitated communication across cultures, the identity of ‘self’ categorized under nationalities and ethnicities have both become a blurred concept. How can we describe the differences between ‘myself’ and ‘themselves’? Where is the line that draws ‘ourselves’ and ‘themselves’? How do we develop our perception of ‘myself’?

Born and raised as a Hong Kong SAR citizen, we naturally embrace the idea also being a Chinese citizen. It does not necessarily follow that a ‘Hongkonger’ is a ‘Chinese citizen’, or ‘Chinese’. In Hong Kong’s football team, the players present different ethnical and racial backgrounds (Cameroonian , Ghanaian, Nigerian, French, British), perhaps having dark or light complexions. They share one thing in common – all recognised as ‘Hong Kong permanent residents’, though they are statutorily not regarded as ‘Chinese citizens’. In statutory and political sense, such difference is reflected by the sheer racial borderline between a Chinese and a non-Chinese. However, in cultural and community sense, the players and I both belong to ‘Hongkongers’. How do we formulate and inherit such conceptualisation? How does the difference between the blood that we are born and the cultures and the community in which we live explain such conceptualisation?

As an ‘Ethnic Chinese’, we can still lead an expatriate life by acquiring expatriate languages and ways of life. We are also born with cultural competence to have a grasp of and realise expatriate lifestyles. The Chinese who I met in the United States were Cantonese speakers, with nothing distinctive in appearance and body figures from Hongkongers. The only difference that tells we are either ‘Hongkongers’ or ‘US citizens’ lies in the manner and acts we display. One interesting point to note is that they tend to take in their identity as a ‘Hongkonger’, even though the communication styles and lifestyles exhibit subtle differences. How do these perceptions come from and perpetuate? If the identity of Hongkonger does not derives from our territory and border, languages, or original nationalities, what are the carriers for self-identification?

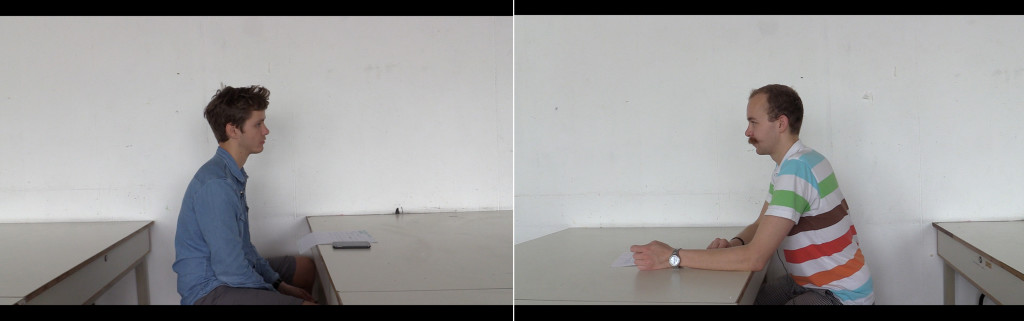

I’ve experienced these struggles and thoughts repeatedly and I wish this series of work can serve as discussion of ‘ego’, self-identity and self recognition as a Hongkonger.